Adding value

Status of 278 MIs

According to section 1(1) of the PAA, a material irregularity (MI) occurs when:

- a person does not comply with or contravenes legislation, engages in fraud or theft, or violates their entrusted duty

- this action can or does result in a significant financial loss, the misuse or loss of a significant public resource or substantial harm to a public sector institution or the general public

- the action is identified during an audit performed under the PAA

When our outcomes include MIs, we can either refer them to public bodies for investigation or include recommendations to address them in the audit report. In the case of the latter, if our recommendations are not implemented, we take binding remedial action. Where the accounting officer or authority does not implement the remedial action, the auditor-general can issue a certificate of debt to recover money lost from accounting officers or authorities.

Status of identified material irregularities

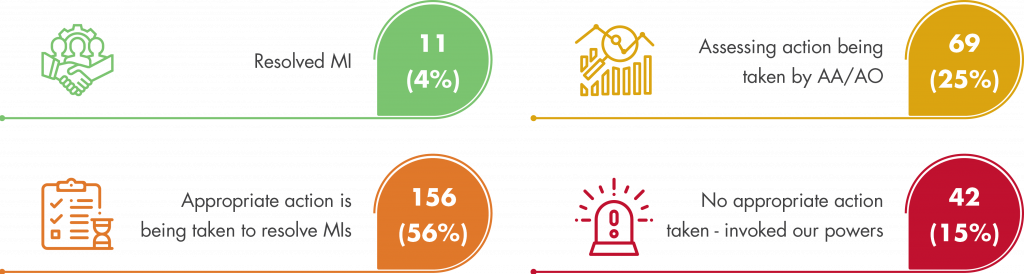

We have either closed or resolved 21 MIs based on information provided by the accounting officer, with 11 resolved over the year.

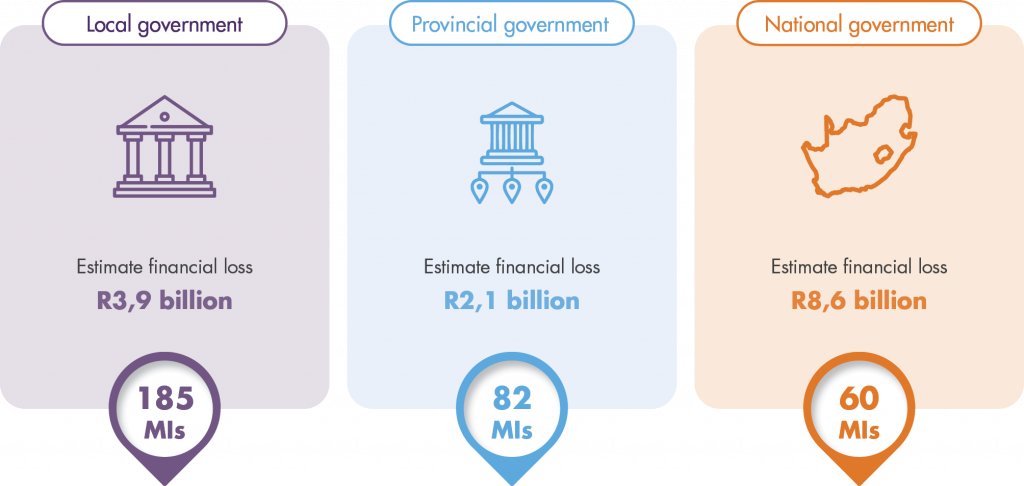

By 15 April 2022, we had a total of 327 MIs on our system at various stages in the process. We estimate the total financial loss of these MIs to be R14,7 billion.

Material irregularities identified per sphere of government

Nature of identified MIs

The spread of the 327 MIs across the provinces (local government and provincial government) and the national government, and the nature of these MIs

We issued our first remedial actions in the performance period to the departments of Defence and Human Settlements, Prasa, and the Ngaka Modiri Molema District Municipality. We also raised MIs for not submitting financial statements for auditing.

We recently notified the accounting officers and authorities of 39 of these MIs. However, our deadline for their response was later than 15 April 2022, which was the cutoff date for inclusion in this report. As 10 MIs were resolved in the previous year, we include the details on the remaining 278 MIs in this report.

Status of the 278 MIs

Although slow, pockets of success are noted. We are beginning to see the MI process unfold as intended, acting as a complementary mechanism in the broader public sector accountability value chain. Most accounting officers and authorities are actively addressing the MIs. In some cases,

- financial losses were recovered or were in the process of being recovered

- internal controls improved to prevent further loss

- disciplinary action was taken against the officials responsible

- fraud and criminal investigations were instituted

- supplier contracts were cancelled.

This demonstrates how our expanded mandate promotes a small, but ever-expanding movement towards:

- better accountability

- protecting state resources

- enhancing public sector performance

- encouraging an ethical culture

- strengthening public sector institutions to better serve citizens and improve their lived experiences.

We also recognised the stumbling blocks that accounting officers and authorities encountered in resolving MIs – some were within their control, but external factors also hampered the process. Those matters within their control included:

- delays in internal investigations to identify the officials responsible and quantify losses

- delays in finalising disciplinary processes against officials

- instability at the accounting officer or authority level.

The external factors hampering MI resolution processes included:

- delays in criminal investigations by the Special Investigating Unit and Directorate for Priority Crime Investigation (Hawks)

- suppliers undergoing liquidation, which hampered recovery

- delays in recovery by the Office of the State Attorney

- delays in resolving matters of intergovernmental processes.

On average, we completed a combined 41% of our audits within legislated timelines. National and provincial audits performed better, with 47% completed, than local government audits with 26% completed. The unavoidable delays and their knock-on effects are mentioned earlier in this section. These effects continued into the 2020-21 local government audit cycle, which began in 2021, while teams were still working on the delayed national and provincial audits.

Outstanding financial statements, financial statements being submitted late and delays in audit process posed further challenges to completing our audits. Audits that were not finalised on time placed excessive pressure on our staff and required significant overtime.

Although we did not meet the legislated timelines, due to the environmental factors, we were able to finalise a high number of audit reports within a reasonable time through close tracking and monitoring. This allowed us to conclude and report on the majority of auditees in the two general reports.

By the end of the 2020-21 local government cycle, we had caught up with our audits.

National and provincial audit outcomes

Our messages in the previous general report, the special reports and through our engagements, were a call to action to strengthen accountability by preventing accountability failures and ensuring consequence management. The theme of the general report was ‘A continued call to act on accountability’.

Some key highlights in the general report:

- We continued auditing infrastructure grant management across sectors in the national and provincial government environment, with the emphasis on health, education and human settlement. The focus was on eradicating infrastructure backlogs at schools to support better learning environments, creating adequate human settlements and rehabilitating health facilities. We recognised an overall weakness in government’s approach to infrastructure projects.

- In this cycle our reporting went a step further by not only highlighting billions of rand in irregular, fruitless and wasteful expenditure but also their impact. These included money wasted, continued shortage of housing, shortage of good schools and poor access to healthcare facilities. Coupled with the poor quality and maintenance of infrastructure, this exposes the public to harm.

- In the midst of a pandemic, the Department of Health becomes critical to citizens’ wellbeing. In this cycle, we highlighted certain key weaknesses such as the medico-legal claims that the sector should focus on, as it has the potential to cripple the state.

- In the human settlements sector we discovered that although grant money provided for building houses or title deed restoration was fully used, uncoordinated planning across the sector left an estimated shortfall of 188 678 houses, 109 843 serviced sites and 1 061 527 title deeds to be transferred.

- We also highlighted that this will further increase the backlog for adequate housing.

We audited 15 SOEs with a total expenditure of approximately R100 billion. Our concern was around their perpetual poor financial health, with significant deficits and lack of funding, and some relying on bailouts for survival. This compromises service delivery, with citizens bearing the brunt of these failings. The report highlights that central to these problems at SOEs are the poor state of corporate governance coupled with a weak internal control environment, instability at a leadership level, non-compliance with legislation and a lack of consequence management.

Overall, the 5% improvement in national and provincial audit outcomes indicates slow progress in the journey towards wholesale good governance. This is particularly concerning in two areas – SOEs and the key service delivery departments of health, education, housing and public works, which have the greatest impact on the lives of citizens and government’s financial health.

Local government audit outcomes

Our messages in the general report were aimed at the new provincial leadership, who took office after the November 2021 local government elections. We urged them to activate the accountability ecosystem to shift the culture in local government towards performance, integrity, transparency and accountability. This could be achieved through courageous, ethical, accountable, capable and citizen-centric leadership. As such, the theme of the report was Capable leaders should demonstrate change by strengthening transparency and accountability.

The general report highlighted these key issues:

- Local government was characterised by accountability and service delivery failures, poor governance, weak institutional capacity, and instability. The number of clean audits slightly increased but the improvement was not widespread.

- Using consultants in addition to available permanent financial officials at a substantial price tag did not provide the intended outcome of submitting financial statements for auditing without material errors.

- Although the economic downturn played a significant role in the dire financial state of municipalities, the lack of basic financial controls causing unbilled revenue and poor debt-collection practices added to local government’s weak financial health.

- Disclaimed audit outcomes, although a technical limitation on the financial statements, are also an indicator of a lack of service delivery in those communities, as observed by our audit teams. These failures have a direct impact on the municipality’s ability to provide water, sanitation and roads infrastructure, which affects the lived realities of citizens.

- After inspecting wastewater treatment works and landfill sites controlled by some municipalities, our experts identified poor, ineffective or limited environmental management, monitoring and enforcement, as well as deficiencies in managing and delivering wastewater and solid waste services. The impact is a significant likelihood of negative effects to both service delivery and the environment.

- We included actionable recommendations to all role players in the local government accountability ecosystem. This extended beyond our usual reflections on the direct assurance providers to include provincial ministries of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs (Cogta) and Finance, coordinating national ministries of Cogta and Finance, provincial legislatures, Parliament, citizens and community organisations.

It is encouraging to see that there has been a slight increase in the number of clean audits – 27 municipalities were able to maintain their clean audit status throughout the term of the previous administration, while 14 achieved a clean audit for the first time and six lost their clean audit status over the five-year period. Clean audits continue to represent less than a fifth of the local government budget.

The real-time audits on the use of the covid-19 relief funds and the use of our audit findings in recovering misused state funds has demonstrated the value of proactive auditing. It has not gone unnoticed and, when the unprecedented floods in KwaZulu-Natal and Eastern Cape struck, the country’s leadership again turned to us to follow the money and assist the executive in ensuring that the relief fund is used for its intended purpose. The real-time audit approach created a space for us to immediately engage, and for management to take immediate corrective action, on matters as and when they were detected. Our multidisciplinary teams, which include financial and specialised audit services, used their diverse skills to gain a holistic view of auditees and their work

Delivering audits through multidisciplinary teams

Using multidisciplinary teams on audits has been one of our 4V strategy’s major objectives to help deliver tailored value to stakeholders. Multidisciplinary teams harness a diversity of skills and expertise to achieve complex audit objectives and gain a deep understanding of our auditees’ businesses. This assists them in navigating the complexities of an environment associated with high expenditure and greater audit risk.

Multidisciplinary teams include professionals in information technology governance, risks and controls systems, data analytics, information security, financial fraud and investigations, and in key government sectors including health professionals, economists, education specialists and engineers.

Their contribution to audit risk assessment, fraud data analytics and specialised auditee knowledge added comprehensive audit insight and improved audit efficiencies and effectiveness. This was again evident in the vaccine audit and helped give the audit team a holistic view of the initiative.

Data analytics intensified during our special audits, with the following key benefits:

- The ability to provide auditors with improved deep insight of the auditee’s operational, fraud and financial reporting risks to reduce the audit risks

- The ability to use intelligent analytics to support the audit process in delivering a higher quality of audit evidence and more relevant business insight and foresight, which assists the auditors to focus the audit on what matters.

- Increased efficiency in audit procedures.

- An assessment of the consistency between audit findings and information available through environmental scanning.

Developing capacity and skills in this discipline aims to increase our real-time auditing and establish data analytics dashboards within the next three years.

Challenges experienced during multidisciplinary audits

While deploying multidisciplinary client-facing teams is our preferred approach going forward, significant challenges need to be resolved to deliver the intended value. The main impediment is the availability of quality data from auditees in a usable format to enable data analytics. We now use a direct link to the auditees’ ERP systems to extract data directly.

Scarce specialist skills, specifically to deal with fraud and investigations, has prompted us to look internally and find innovative ways to capacitate our teams.

Standalone audits

Standalone audits are focused audits that drill down into an identified topic to unearth the root causes of mismanagement, irregularities or lapses in service delivery. These projects do not span a performance year but could cover the lifetime of a project or the period of the alleged irregularity or mismanagement.

Investigations

We assess requests for investigations and undertake those that fall within our mandate. These requests are put through the annual audit process and, in many cases, are addressed during the audit. However, in cases where the merits of a request cannot be resolved during the audit process, we undertake a separate standalone investigation.

We continued to respond to those requests outside our mandate by referring the complainant to the relevant public bodies that are better equipped to deal with these matters through their mandates and raising awareness of the types of matters that our mandate covers.

Performance Auditing

The follow up performance audit on the rehabilitation of derelict and ownerless (D&O) mines was tabled on 30 March 2022. This 2021 follow-up audit evaluated the department’s progress since our previous audit in 2009, focusing on whether the issues highlighted in the previous report still exist.

The audit revealed that progress has been very slow and has had an impact on the environment and communities located close to these mines. These unrehabilitated D&O mines and mine openings often cause air pollution from dust or toxic gases, infertile soil and severely degraded water resources that are often devoid of life.

Illegal mining also contributes to these issues as it uses unsafe mining methods and threatens the viability of government’s holing programme, as the illegal miners open previously sealed mine openings. The Follow-up performance audit at the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy on the rehabilitation of derelict and ownerless mines has details of our findings and the department’s commitments to resolving the findings raised.

Review of our audit programme for relevance and efficiency

We annually reflect on our audit approach and priorities to ensure that they remain relevant and use the latest technical and technological developments.

A key audit focus, identified during our tactical audit dialogue, is poor infrastructure project management and its impact on disadvantaged communities. We will implement a focus on this area in the upcoming audit cycles.

By implementing a differentiated audit approach, where the depth of audit is aligned to the prominence, size and impact of the auditee, we improve our audit efficiency and effectiveness in the areas that have the most fundamental impact on people’s lives.

In 2021-22 we developed three new methodologies for the annual financial statement review engagements aligned to ISRE 2400, audit of predetermined objectives findings engagements, and compliance findings engagements. We trained our teams to test these new methodologies at pilot audit sites during the national and provincial 2021-22 cycle.

We piloted a limited assurance audit of predetermined objectives approach at selected municipalities during the 2020-21 local government audits, which allowed us to achieve efficiencies in audit hours and audit staff levels without diminishing the quality of the audit work. Based on the feedback from the 2020-21 local government pilot on the audit of predetermined objectives limited assurance approach, we saw an average of 42% reduction in audit hours. We will extend this approach to the 2021-22 local government audit cycle using the lessons learnt during this pilot.

In line with our new #cultureshift2030 strategy, we plan to enhance our approach to auditing predetermined objectives in a way that helps equate an auditee’s achievements with its mandate.

Review of our audit portfolios for maximum added value

After in-depth preparation over the last few audit cycles, we have taken over and signed off on the Transnet audit for the first time in 2021-22.

We intend to take over the Eskom audit in the next few years, once we have created the necessary capacity and capability for such a complex audit. Our preparation includes stronger governance over the work of private auditors, seconding AGSA staff to the audit and taking over sections of the audits in a planned staggered approach.

After we completed all our activities for the 2020-21 Eskom audit, the appointed auditors addressed all significant review observations before the finalising the audit report. The scope of our assignment had a specific focus on key high-risk areas and areas of public interest.

Currently we audit 15 of the 21 schedule 2 entities. We are continuously assessing the audit risks of the remaining schedule 2 SOEs and our plans include taking over two further audits.

To improve our efficiency and capacity, we assessed 43 museums that we currently audit against their governing legislation. Of these museums, 24 are governed by legislation that requires us to be their appointed auditor. We have opted out of auditing 19 provincially funded museums in line with section 4(3) of the PAA.

Strict oversight of governance in section 4(3) audits

In cases where we have opted not to audit specific public entities, we have included a comprehensive set of measures to enhance the governance around appointing private audit firms as external auditors for these entities. Our observations on the adherence to our requirements show that these measures, described in our regulations, are now comprehensively understood and applied by most of our auditees.

At entities where we opt out of auditing, we enhanced our review process with a due diligence exercise of all partners from the private audit firms chosen for the audit. The partners that did not pass the review were excluded from signing off on section 4(3) entities’ audits. We implemented concurrence conditions for those identified as ‘high-risk’ audit firms to adequately mitigate the risk.

Proactive quality support reviews

Proactive reviews are conducted by our technical audit support during the audit and are limited to specific areas in the audit files where audit quality risks have been identified.

Part of the proactive review is for reviewers to engage with the audit teams to influence a higher quality on their audit files. Proactive reviews also identified audit quality findings in compliance, reporting and concluding. The audit teams resolved these findings prior to signing off the audit reports.

Details of these findings were also shared across the organisation to ensure that similar audit quality matters are addressed on audits that did not undergo a proactive review.

The proactive reviews on a selection of national and provincial, and local government audits implementing the MI process were part of a wider support plan for those audits that included internal peer reviews and external pre-issuance reviews.

In 2021-22 we conducted biannual performance evaluations of pre-issuance reviewers, who play an important role in ensuring the quality of the audit file. Pre-issuance reviewers that did not pass the assessment were removed from our database for a minimum of one year. We also sampled the work of engagement managers in a review gap period to ensure that we maintain audit quality.

Prepare the organisation for implementing the International Standards on Quality Management

ISQM 1 will replace ISQC 1 on 15 December 2022. The standard is intended to strengthen audit firms’ quality control systems. We have made substantial progress in preparing the organisation for implementing the ISQM.

We allocated roles and responsibilities to the respective officials and structures, although the ultimate responsibility lies with the deputy auditor-general and operational responsibility lies with our exco. We also included a commitment to ensure the quality of our audits in our strategic documents. Our teams finalised the ISQM risk profile and conducted continuous risk assessments, which is a significant highlight of the ISQM journey. This is detailed in the vision and values chapter. We have started the preparatory work required for the system of quality management (SOQM) documentation. Overall, despite some internal challenges, the project is on track.

For 2021-22, we received 29 complaints that fell within our mandate. The majority of the complaints were received through the AGSA’s website.

The trend of the public expecting us to solve their complaints or disputes with third parties is likely based on the AGSA’s reputation as a Chapter 9 institution. However, these complaints are outside our mandate, which is communicated to the complainant.

Ten complaints, classified as category 3, were referred for resolution to the respective process owners who were considered subject matter experts. These referrals were only in cases where there was no risk of compromising the independence of the complaints process. This helped improve turnaround times in resolving complaints.

Of the complaints received in 2021-22, 19 were investigated, 9 were finalised and the rest are still in various stages of progress. In addition, we finalised 42 complaints that were carried over from the previous periods (34 from 2020-21 and 8 from 2019-20). As at May 2022, we had 14 cases from previous periods in the final stages of reporting.